My grandfather, James Shonts Eriksson, became a lawyer in Fergus Falls, MN, after graduating number one in his law school class at the University of Minnesota in 1933. Shortly before WWII he was settling an estate involving 32 heirs to 120 acres of woods near his lake cottage north of Fergus Falls. None of the heirs would talk to each other, but they would talk to him. His solution for settling the case was to buy the individual shares of property from each heir, and thus he ended up owning the entire 120 acres. The land included a small shack with a dirt floor, where a squatter named Louie was living. Grandpa allowed Louie to continue living on the woodlot and paid him to do odd jobs, such as chopping wood.

In the mid 1940’s my grandfather’s friend, Pete Nelson, came up with the idea of producing maple syrup in the woodlot. Pete worked for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Fergus Falls and shared common interests of hunting and fishing with Grandpa. Later he married my Grandma’s sister Ruth and they moved to Juneau, Alaska. Before that happened, Pete and Grandpa arranged to cut and mill trees on site into lumber, and then built an 18’ by 40’ building with a 12 foot wide lean to. The biggest maple syrup evaporator available was installed that burned standard four foot long “cord wood”. By this time Louie was long gone, but his shack was relocated next to the new building and was used for the syrup operation.

Two gallon metal containers that had been used to store liquid eggs were obtained from the bakery and repurposed to collect sap. They were hung from spiles tapped into the maple trees. You can find a few of those containers laying around in the woodlot today. At some point the metal containers were replaced by 2.5 gallon vinyl bags that were also hung from the spiles. Depending on the amount of snow, a team of horses pulling a sleigh, or a tractor pulling a wagon, towed 250 gallon tanks through trails in the woods. Sap collected at each tree was emptied manually into five gallon pails. Four bags of sap would fit into two five gallon pails, which the helpers then lifted up over their heads and dumped into the top of the tank on the wagon, usually slopping some out in the process. This was hard labour and usually involved working in cold and wet conditions, trudging through deep snow or slipping around on mud, while carrying and emptying the heavy containers of sap. A crew of Grandpa’s syrup workers included his sons, along with local grain and dairy farmers who were in their off season and got paid $1.00 per hour.

The tanks of sap on the wagon or sleigh were driven up a gravel ramp where a pipe with a swivel attached was used to get the sap down into a 1,200 gallon storage tank. This final large storage tank was connected to the evaporator by a transfer pipe through the wall of the building. A float valve controlled the amount of sap flowing into the evaporator. The sap was then cooked down into syrup.

At one time as many as 2,500 trees were tapped, resulting in 25,000 gallons of sap and 650 gallons of syrup, which was sold to a wholesale distributor in Onamia, Minnesota. This went on into the 1960’s, when my uncles graduated from high school and were no longer around to help.

In the 1970’s a neighbor was allowed to tap trees in the woodlot and make syrup using our family equipment, in exchange for a percentage of the syrup and some split wood. After my Grandpa died, my Grandma lived at the lake and used firewood for her wood burning furnace, so this was a big help.

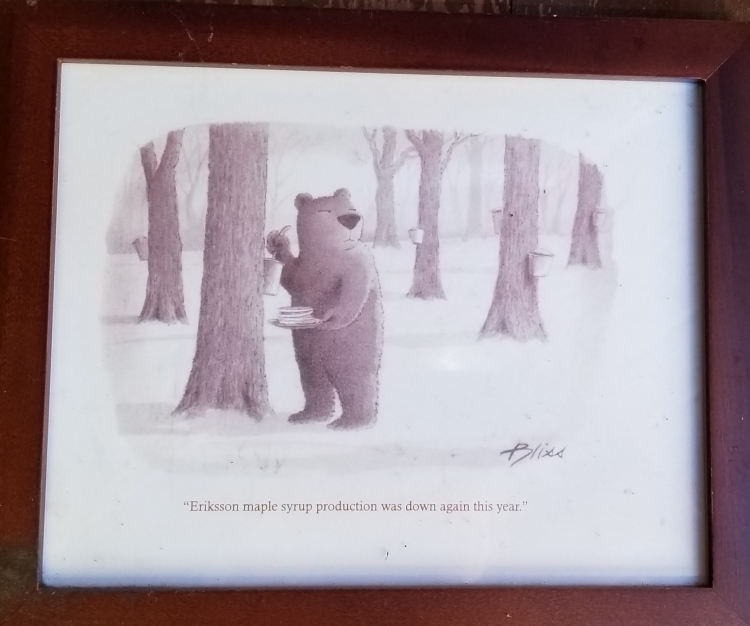

That original syrup building was still standing as late as 1982 when I first brought my future husband to the lake. There is a photo of the two of us standing in front of it from that era. Notice I am wearing my Frostline Kit down vest that I wrote about in an earlier blog post (click here to read that post). Sometime in the mid 1980’s, after Eriksson maple syrup production was just a memory, the building finally collapsed.

In the early 2000’s there was a bad storm with straight line winds that knocked down hundreds of trees in the woodlot. The idea of restarting a syrup operation was floated around. My uncles polled all the siblings and next generation cousins to see if there was any interest. There seemed to be enough willing helpers, so they went ahead with preparing the site for a new syrup building. A guy with a Woodmiser portable sawmill came and milled lumber from oak, ash and maple trees. The 30’ by 60’ building was constructed, consisting of a 30’ by 16’ evaporator room and space for storage of wood and various equipment. The cement floor was poured in the evaporator room in 2007, the floor in the storage area was left as dirt. In 2008 an evaporator was purchased for $14,000 from the Leader Evaporator company in Vermont. It came on a truck in pieces and had to be assembled with much trouble from cryptic instructions and unhelpful phone calls to the company. Rather than using buckets or bags for collecting sap, plastic tubes were strung through the trees, going gradually downhill towards the syrup building. Note that the Eriksson clan does not do anything on a small scale.

The making of maple syrup in the spring became a renewed Eriksson family tradition, attracting relatives from across the country as well as friends interested in the process and getting out in nature after long winters. In late March and early April, depending on the weather, trees are tapped and the plastic lines attached to the spiles. The sap flows by gravity into larger tubes and then into four storage tanks in the woods, and from there it is pumped into a transfer tank on the back of the truck. Sap is then pumped through a filter up into a larger tank on a platform outside the building, and finally, by gravity and using a float valve, the sap flows into the evaporator. It took several years of trial and error, and refinements in the system and equipment, before it all worked efficiently.

The sap in the large collection tank outside the building is cold, so it takes a long time to get it up to the right temperature while cooking. One of my cousins had the idea of installing a “pre-heater” tank just inside the building, where the sap could warm up using heat from the chimney before entering the evaporator, thus making the cooking process much more efficient. Interestingly, an east wind can reduce efficiency by as much as 25%. This is likely related to increased moisture in the air.

While the sap is cooking in the evaporator, someone has to sit there for hours and watch the temperature dial. At 219 degrees it is syrup, and the person “draws” it out by opening a valve that allows the syrup to flow into buckets through a type of filter used in the milk industry. After that step, the syrup is poured through another filter into 10 gallon stainless steel containers. It goes from there through yet another filter press. Finally it drains into a stainless container where it is brought up to 180 to 200 degree canning temperature, then out a spigot into one pint and one quart plastic jugs. Caps are put on the jugs, and the jugs are placed upside down to seal.

Last year the syrup team experimented with using food grade plastic buckets for collecting the sap instead of the plastic tubing method. A short length of plastic tube connects to the tree tap, with the other end going into the bucket sitting on the ground. The buckets get manually emptied through a filter into a larger container and then pumped into a transfer tank on the back of the pickup truck, like the old days but with better equipment. After that the process is the same.

After canning of syrup is complete, there is a big cleanup process. The plastic tubes have a cleaning solution and then rinse water run through them. All the buckets and covers and lids are washed with a cleaning solution used in the dairy business, then rinsed, dried, and put away for storage until the next season. The short lengths of tubes attached to the spiles are run through the dishwasher, followed by a rinse with fresh hose water outside. The evaporator and other equipment and fixtures in the syrup building are all washed and cleaned up, and all tools put away.

During the off season, and in preparation for a new season, there is a lot of maintenance. Sometimes fallen trees have to be cleared from the trails. There is always wood to be cut, split, and stacked in the syrup building, where ideally it dries out for about three years until it is ready for fuel in the evaporator. Between syrup seasons, the plastic tubes start to sag, trees fall on them, and animals chew through them, causing necessary repair and straightening out. Before tapping the trees, the tubes must be straightened out and fresh water is run through them to make sure they are clean.

Using the plastic tubes versus buckets for collection of sap each have their pros and cons with different issues and labor needs. Sap can run through the lines into collection tanks continuously whether there is a person there or not. As much as 900 gallons can be collected in a couple of days using the plastic tubes with ideal conditions. But sometimes the lines freeze, stopping the sap from flowing, and they require more maintenance between seasons. With the bucket method, there is less maintenance needed during the off season, but more people are needed to set up and collect the sap in a short window of time when the sap is running. Some sap is wasted if not all of the collection buckets are ready to go at the same time, some are emptied when only partially full, and others overflow before being emptied. It is time consuming to clean the buckets, as opposed to a two hour job of running water through the lines.

This year 220 buckets were used, and the plastic lines were left to sag in the woods. The conditions were right for the sap to flow at the right time, with comfortable weather for working outside during the day. There was no snow in the woods, there were enough people. The total amount of sap collected was around 1,300 to 1,400 gallons, resulting in about 30 gallons of syrup. It was very warm outside when all the cleaning of buckets happened with cold hose water. It was fun working outside together and we even used a little of the fresh syrup for a pancake breakfast in the woodlot.

Maple syrup harvesting can be and has been a fun family bonding experience, but it is not without challenges and is not a cost effective way to get syrup. Problems have included the many hours of maintenance needed to keep the equipment and lines in working order, having enough labor at the right time (or at all) to get all the tasks done without a couple of people being stuck with most of the work, weather which can disrupt the sap flow and/or make it difficult to collect the sap if snow and mud interfere.

Ideal conditions for sap to flow are temperatures below freezing during the night, and above freezing with sunshine during the day. Normally that happens in March, but the weather can vary from polar vortex to summerlike conditions. Some years the weather has not been right for sap to flow when the helpers are available, or sap is flowing before the equipment is set up and ready.

Climate change since the original Eriksson Maple Syrup years has had a significant impact on the harvest. Spring weather has become warmer and more unpredictable, and reduced the amount of time the sap runs from a couple of months in the 1940’s and 1950’s to around two weeks today. Also, the water table has risen significantly in the woodlot, causing mature trees to weaken and fall, causing more work clearing trails and repairing sap lines.

Restarting Eriksson Maple Syrup production 20 years ago was the rebirth of an Eriksson family tradition. Multiple generations of Erikssons gather in the woodlot after a long winter, and enjoy the camaraderie and being outdoors. Not to mention the fruits of all that labor, excellent quality maple syrup.

The enthusiasm for the annual tradition, however, has waned a bit over time. The novelty has worn out, and some years it has been hard to get volunteers. Fewer volunteers means the people who do show up do more of the work. One option being contemplated is to gather syrup every other year, since there is typically syrup left over from prior harvests. Hopefully the next generation of Erikssons will keep the tradition going.

Oh Meg – this was Wonderful! Thank You for sharing such an inspiring family story. I think it is definitely publishable beyond your blog. What a lucky family to have such an awesome, binding tradition. XXXOOO – Diane

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope we can keep the tradition going with the next generation!

LikeLike

I love this story Meg. I’ve always been interested in it, and when you mom said how much work it was she certainly was right and it’s much more work than I imagined.

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad you like the story! It is a ton of work for sure, which usually falls on a couple of people.

LikeLike

Love hearing about your family & the sap business! Learned a new word: stiles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked the post! The new word is “spiles” with a “p” but you got me checking the draft to make sure I did not make a type! haha.

LikeLike

Wow! I never knew it was such a process! I hope your family tradition continues, but I can see where it could be a struggle. I shall never complain about the cost of maple syrup again! Thanks for a very informative post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think a person could collect a couple of buckets of sap and boil it on the stove. But as I said, my family does things on a big scale!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great story! I was so excited to read that production had started up again. I really hope your family is able to continue this venture. I am a huge fan and always buy local. It costs a bit more, but boy is it worth it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comments! Sometimes the whole thing seems like too much of a hassle, but the family bonding part makes it worth it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was very interesting! My cousin has a sugar shack on his property and it takes a lot of sap to produce one bottle of syrup. Great story

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you…yes it is close to 40 gallons of sap for 1 gallon of syrup!

LikeLike

Now we know why real Maple syrup is so expensive!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great story, very well written Meg.

It seems very rewarding!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just learnt so much from this post but man what a LOT of work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No kidding! Thanks for reading!

LikeLike